Older OOP

This appendix discusses the older OOP syntax. We won't use it in CS 204, but it can be worth learning.

Classic Syntax¶

Let's revisit our ball example but without the helpful syntactic sugar. Remember that the ideas and implementation is the same.

function Ball(color, radius, hasPolkaDots) {

this.ballColor = color;

this.ballRadius = radius;

this.doesThisBallhavePolkaDots = hasPolkaDots;

};

Ball.prototype.getColor = function() {

return this.ballColor;

};

Ball.prototype.setColor = function(color) {

this.ballColor = color;

};

Ball.prototype.bounce = function () {

console.log('currently bouncing');

};This defines a constructor (the Ball function) and three methods, all

defined as functions stored in the prototype property of the

constructor. Very different from the new syntax, but means the same thing.

Interestingly, the code to use the Ball class is exactly the same:

// examples of creating two instances of the class

var b1 = new Ball("Red", 12, true);

var b2 = new Ball("Blue", 5, false);

// examples of invoking a method

console.log(b1.getColor()); // "Red"

b1.setColor("Green");

console.log(b1.getColor()); // "Green"

// example of retrieving an instance variable

// it would be better to define a method to do this

console.log(b2.ballRadius); // 5

b1.bounce(); // Booiiiiinng. Ball is bouncing

b2.bounce(); // Booiiiiinng. Ball is bouncingYou can see that code in action using the ball classic demo. Again that the web page will be blank. View the page source to see the JS code, and open the JavaScript console to see what was printed to the console.

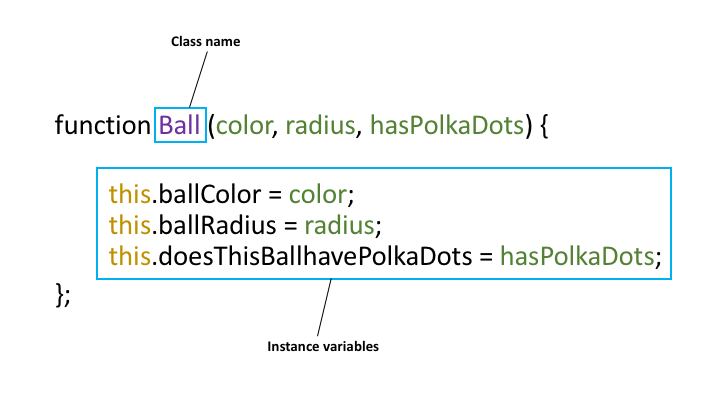

Let's break the code into sections. The first 5 lines of this code are:

The class name is Ball, as indicated by the box and purple in the

picture. By convention, class names are always capitalized. When creating

a Ball using new, it needs to be given a color, a radius, and whether or

not it has polka dots, as shown by the green. The code with the keyword

this indicates that you are storing the green parameters

(color, radius, hasPolkaDots) to the instance variables (ballColor,

ballRadius, doesThisBallHavePolkaDots). The instance variables describe

the properties or state of the object, as described earlier in this

reading.

Comparing this to the modern syntax, we see that the capitalized function plays the role of both class and constructor function.

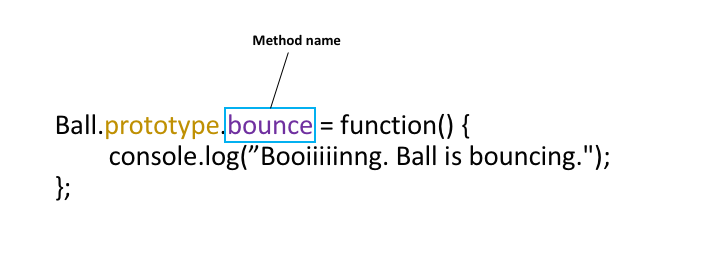

Now let's turn to methods.

Just as instance variables describe state, methods describe the

behavior of the object. Here, the name of the method is bounce as

indicated by the box and the purple. When a ball bounces, it logs

"Booiiiiinng. Ball is bouncing." When you create new methods, you always

preface the function with the name of the class (in this case, Ball) and

the key word prototype.

Comparing this to the modern syntax, we see that methods are defined as properties of the prototype property of the class (constructor function). Every instance gets the class as its prototype, so putting methods as properties of the prototype means that every instance gets those methods.

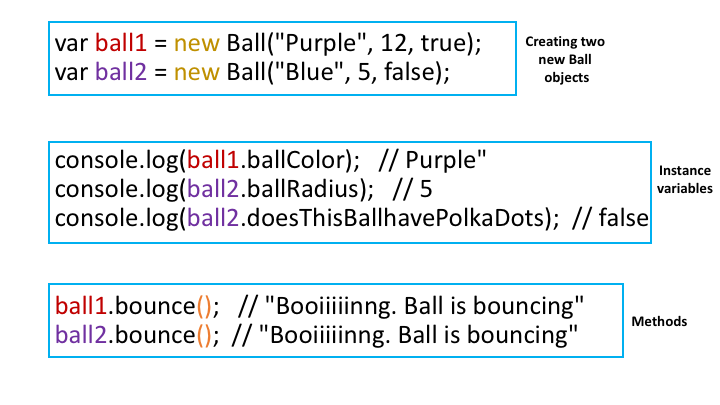

Here are some examples:

After you create the Ball class, you can create specific instances of

Ball objects. The first two lines of code create b1 and b2, each with its

own characteristics. Notice that when you create brand new objects, you

must use the keyword new. The next three lines of code

accesses the different instance variables. For example, b1 is

purple. Finally, the last two lines of code access the method of the Ball

class. Both b1 and b2 have the method bounce, so they will behave the

same way. Notice that when you access methods, you must use parentheses

at the end! (as shown by the orange).

Furthermore, if you compare the old syntax with the new, you'll see that using OOP (creating instances and invoking methods) are exactly the same between the two. The new syntax just makes it easier to describe the class, its constructor and methods.