Constructors, this, Methods and Bind

This reading is supplemental to Chapter 8 (page 183 to the end).

Invoking a Constructor¶

As you know, a constructor should be invoked with the keyword new in

front of it. Like this (this version of bank accounts require specifying

the owner) invocation:

var george = new Account("george",500);

The new keyword causes a new, empty, object to be created, with

its prototype set to the prototype property of the constructor.

What happens if we forget the new? Open up a JS console for this

page and try the following:

var fred = Account("fred",500);

Print the value of fred. Print the value of balance

What happened? Here's a screenshot from when I did it:

The balance global variable is initially undefined. The fred

variable is undefined, because Account returns no value, and

balance is a new global variable, because this meant the global

object (essentially, window).

All because we forgot the new keyword!

FYI, if you want to protect against this error, make your constructor like this:

:::JavaScript

function Account(init) {

if( this === window ) {

throw new Error("you forgot the 'new' keyword");

}

this.balance = init;

}

The THIS variable in normal functions¶

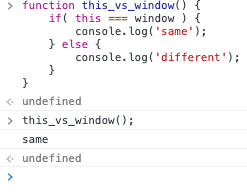

Here's another aspect of the weird properties of this. In normal

functions, the variable this is bound to window. Try it:

function this_vs_window() {

if( this === window ) {

console.log('same');

} else {

console.log('different');

}

}

Here's the screenshot:

Basic Method Invocation¶

As we saw earlier, methods have access to this. Here's the example:

:::JavaScript

function Foo(z) {

this.z = z;

}

Foo.prototype.sum = function (x,y) { return x+y+this.z; };

var f1 = new Foo(1);

f1.sum(2,3); // returns 6

The syntactic rule is that whenever we invoke a method, the special

variable this gets bound to the object, which is the thing to the

left of the dot.

Method Invocation Bug¶

Here's a way that method invocation and the value of this can get

messed up. Imagine we add a method to our bank account that will help

us set up a donation button on a page. That is, it'll add an event

handler to the button that will deposit 10 galleons into the

account. Here's our attempt:

Let's take a moment to understand that code: 1. The method is going to add some code as an event handler to a button. 1. The button's ID is passed in to the method. 1. The event handler (which is invoked when the button is clicked) adds 10 galleons to this account.

So far, so good.

Let's use this new method to create a donation page for poor Ron. Here's the button and its code:

Here's the code to add a button handler to help Ron:

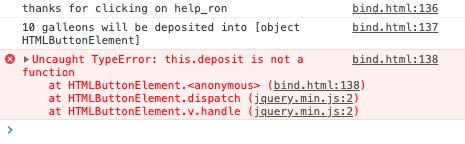

Try it! Click the button to help Ron, and look in the JS console at the error message. Here's the screenshot of the error I got:

The error is a little hard to understand. It literally says

"this.deposit is not a function". But in our code above, in

add_donation_handler, the variable this seems to be the bank

account. But what happened is that, in the event handler, the value of

this is the button element that was clicked on, not the value it

had in the add_donation_handler method (namely, Ron's bank account).

The trouble arises because this is constantly changing value. Here,

the event handler was invoked, which is a function call, and (as we

learned earlier in this reading), this changes: Rather like the

pronoun me which means a different thing for each person who says

it.

THIS is Slippery

The value of this changes:

- when a function is called

- when a method is called

- when an instance is created with

new

Closures to the Rescue¶

Hang on, isn't the event handler actually a closure? Yes, it is. It has

two non-local variables, namely buttonId and this. The buttonId

variable has its proper value, but not this.

That's because this is special: It is not closed over.

However, almost any other variable can be closed over. Traditionally,

JavaScript programmers use the variable that. Here's an example:

The code is nearly identical to our earlier add_donation_handler

method. The difference is that we create a local variable called

that, assign the value of this to it, and then create the event

handler referring to that instead of this.

Here's the button and its code:

Here's the code to add a button handler to help Ron:

It works! Try clicking the button, and you'll see that each click increases Ron's balance. You can also open the JS console and check his balance yourself. Here's what I saw after clicking the button twice:

So the that trick works.

The bind method¶

The need for the that trick is so common that JavaScript added a method

to the language to solve it in a general way, without tricks like that.

If I take any function and invoke the bind method on it, it returns a

new function that has the given value as the value of this. Here's an

example:

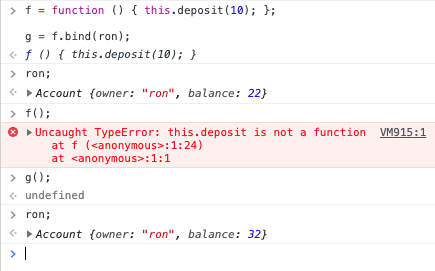

:::JavaScript

f = function () { this.deposit(10); };

g = f.bind(ron);

If you invoke f, you'll get an error, because this has no value. If

you invoke g it'll successfully add 10 to Ron's bank account.

Try it in a JavaScript console! Copy/paste the definitions of f and

g and then invoke them. Here's a screenshot of what I got, showing

Ron's balance before and after, the error from f and the success

with g:

Go back and compare f with the event handler in add_donation_handler,

you'll see that they are the same (if you remove all the console.log and

alert statements). So the bind method will solve our trouble without

having to use that. Here's how:

The code using bind is nearly identical to our first

attempt, except near the end, where the anonymous function

that is the argument to .click() has .bind() invoked on it, to

nail down the value of this.

What's weird and confusing about the code is that we are binding the

value of this (inside the anonyous function) to the current value

of this (outside the anonymous function). So it sounds like a

tautology, like saying x=x. It's not a tautology because of the

slippery nature of this. We know that, without using bind, the

value of this would change from the outside to the inside.

Let's try it. Here's our last button to help Ron:

Here's the code to add a button handler to help Ron:

So, using bind is simple and easy. It just hard to understand,

because what it's doing is so very, very abstract.

What bind does¶

Let's recap:

bindis a method on functions- its argument is a value for

this bindreturns a different function- the return value is just like the argument function except that is has a fixed value for

this

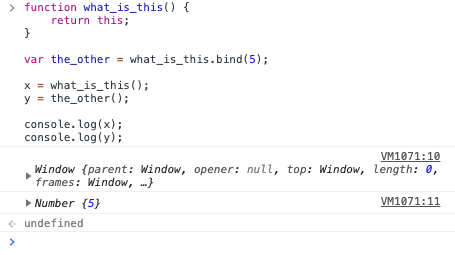

Here's an almost silly example. It's silly because you'd never do this

in real life. It's useful because it shows how bind fixes a value

for this. ["fix" in the sense of "fasten securely in place" rather

than "repair"]

function what_is_this() {

return this;

}

var the_other = what_is_this.bind(5);

x = what_is_this();

y = the_other();

console.log(x);

console.log(y);

Here's what I get when I copy/paste that code into the JS console:

The first return value is "window" as we saw at the top of this

reading. The second is 5, because we used bind to nail down that

value.

Copy/paste the silly example yourself.

The real-life uses of bind are what we saw with the button to help

Ron: we had a function that needed to refer to this but we knew that

the value of this would change, so we needed to nail it down.

The Bug from Chapter 8¶

Our book created a common and tricky bug to illustrate this subtle issue

with this and method invocation. They did an excellent job of setting up

the bug and motivating the use of bind in only a few lines of code.

We'll go over it in class, but here's some preparation:

Buggy code¶

The situation with the buggy code on page 183 is inside a method

definition, so we have a value for this but then we want to invoke a

method on some other object, and that changes the value of this:

:::JavaScript

// This is the buggy version from page 183

Truck.prototype.printOrders_buggy = function () {

var customerIdArray = Object.keys(this.db.getAll());

console.log('Truck #' + this.truckId + ' pending orders:');

customerIdArray.forEach(function (id) {

console.log(this.db.get(id));

});

};

Debugging¶

Let's learn how to use the Chrome Debugger. (Debuggers in other browsers work similarly.)

We can replicate the bug with the function bugSetup that I implemented

for us, to avoid a bit of typing. We'll look at the definition first:

:::JavaScript

var myTruck;

function bugSetup() {

myTruck = new App.Truck('007',new App.DataStore());

myTruck.createOrder({ emailAddress: 'm@bond.com',

coffee: 'earl grey'});

myTruck.createOrder({ emailAddress: 'dr@no.com',

coffee: 'decaf'});

myTruck.createOrder({ emailAddress: 'me@goldfinger.com',

coffee: 'double mocha'});

}

This code just creates a truck (in the global variable myTruck) and

creates some orders so that there is something to print.

Using the Chrome Debugger¶

I'll visit this coffeerun app with the bug, which opens in another tab/window.

Then, we will try the following method invocations:

bugSetup();

myTruck.printOrders_buggy();

Debugging Steps:

- Set a breakpoint at the line of the error

- show that

escopens/closes the drawer - run

myTruck.printOrders_buggy()again - try pieces of the code, like

id,this.db.get(id)and so forth in the console - click up/down the call stack and try them again

- resume execution

- remove the breakpoint

- re-run the code to make sure the breakpoints are gone

Chrome seems to remember the breakpoints forever. I've had Chrome jump into the debugger when I'd set the breakpoint the previous semester. It's pretty easy to remove the breakpoints and resume the code, but it can be confusing to end up in the debugger when you didn't expect to.