Security

There are two separate but important topics in this reading on security:

- HTTPS

- XSS

There are also a few short, miscellaneous security-related items.

HTTPS

HTTPS is a protocol for secure transmissions between browser and server.

It's based on public key encryption, which we talked about earlier

in the context of passwordless SSH connections and passwordless

uploads to Github. It's a similar idea. If you'd like to brush up,

here are some links:

- Encryption

- Certificates

- Humorous but informative take on Digital Signatures

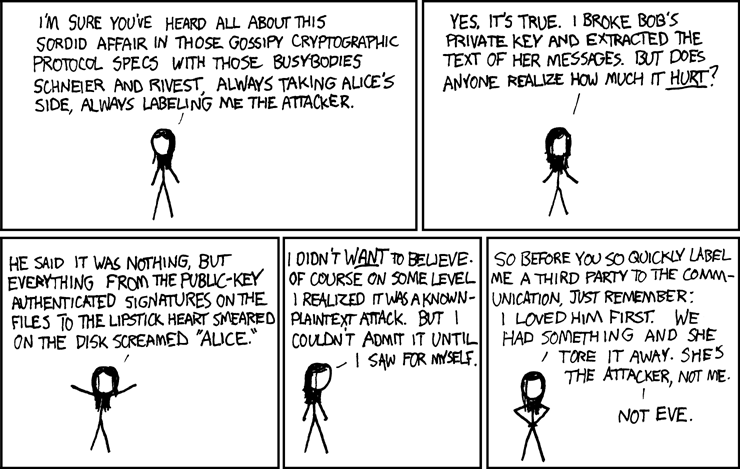

- And a funny XKCD cartoon about public key encryption:

The important ideas for HTTPS are these:

- The browser requests the server's public key.

- It checks the authenticity of the public key by checking that it has been digitally signed by a known Certificate Authority (see next section)

- It creates a session key and encrypts it with the server's public key

- It sends the encrypted session key to the server.

- The server decrypts the session key and then both browser and server can use the session key to encrypt all their subsequent communications.

It's simple to use: just make your links use HTTPS instead of HTTP. A few warnings:

- If you visit a page using HTTPS, Google Chrome (and maybe other

browsers) won't load certain supporting files using the insecure

HTTP protocol. So all

LINK,SCRIPTand other loading has to use HTTPS. If someone visits the page using HTTP, loading supporting files using HTTPS is okay. (Chrome complains aboutIMGtags over HTTP, but will permit it. You can look at the console log in this page to see where it loads several XKCD cartoons over HTTP instead of HTTPS. Not all servers have HTTP, and when I first did this, XKCD did not. Now it does, so I could upgrade, but I haven't so that you can see what happens.) - A change from HTTP to HTTPS will violate the

Same Origin Policy

that we discussed in the context of Ajax. (That's because Apache listens for HTTPS connections on port 443, not port 80, so it's a change in port.) So if someone visits your page using HTTP and you try to do some Ajax stuff using HTTPS, it'll fail.

SSL with Flask in Development Mode¶

You can use SSL (essentially, HTTPS is HTTP + SSL) in Flask in development mode.

app.run('0.0.0.0',port, ssl_context='adhoc') (See Miguel Grinberg: Running Flask App over HTTPS.) In particular, Grinberg warns us that:

Simple, right? The problem is that browsers do not like this type of certificate, so they show a big and scary warning that you need to dismiss before you can access the application. Once you allow the browser to connect, you will have an encrypted connection, just like what you get from a server with a valid certificate, which make these ad hoc certificates convenient for quick & dirty tests, but not for any real use.

However, you don't have to do this. I almost never do. However, I do

make sure that external links all use HTTPS. Internal links, of

course, are generated using url_for().

Note that, as of this writing (October 2020), Chrome will sometimes allow you to use HTTP, but sometimes it decides to insist on HTTPS, and will refuse to connect to your app over HTTP. Many students have run into that issue in the Fall 2020 term. All of them were successfully able to run their app over HTTP using Firefox, Safari, or Edge.

Certificate Authorities¶

A certificate authority is a corporation or organization that digitally signs the certificates (like public keys) that are used in HTTPS. Wellesley's Certificate Authority is In Common.

Look in your web browser to see what certificate authorities it trusts.

- Firefox: look under Preferences > Advanced > Security > View Certificates > Authorities.

- Chrome: Settings, Advanced Settings, HTTPS/SSL. On a Mac, this accesses the Keychain.

- Safari: on the Mac, go to Applications/Utilities and open Keychain Access. Then Window/Keychain Viewer.

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks

The security issues when modifying the database (INSERT and UPDATE) are much worse than merely reading data (SELECT), because the malicious user could put in data that indirectly attacks other users. This is an XSS attack: Cross-Site Scripting attack.

The idea of XSS is similar to SQL injection in that the malicious person manages to get data treated as code and executed. However, instead of the code being SQL code executed by the DBMS, it is JavaScript or HTML code that is executed by the victim's browser. Your database is just a transmission vector.

An example is a web application that allows "user comments" (like for certain articles on the www.nytimes.com website). The malicious user (Mallory) puts some code in their comment, which is then executed by the victim's browser when they (Vicky) read the article.

The following figure illustrates the idea:

The solution to this attack is to encode the characters that go to the browser, so that it won't be executed as JavaScript. (There are some additional complexities that we will get to later in the course, if we have time, but this will be a good start.)

The most common scenario is that your web application puts some text from the database into some static HTML:

text = row['comment'];

return render_template('something.html', var=text) What happens if text is some of the following?

<img src="http://nasty.xxx/">

<script>window.location = 'http://nasty.xxx'</script>

<em onmouseover="window.location = 'http://nasty.xxx';">

mouse over me!</em> When and Where to Encode?

Should you encode the text when you put it into the database or when you take it out and send it to the browser? Either could be okay. You might want to be able to send the literal user input to a file or some other place where a browser won't execute it, in which case you might want to wait.

However, a common practice is to encode on display and allow the malicious code into the database. Why? One possibility is that the code is not really malicious, it might be exactly what the user intended. What if someone enters <jk> into a comment? You'd like the reader to see that, rather than have either (1) the browser get confused or (2) the text to be removed.

Or, another example, what if some aspiring screenwriter writes a movie named this:

<script> If we insert that into the WMDB, we probably want the angle brackets to be in the database, rather than

<script> Flask uses the approach of encoding something on display. It does this automatically (by default). In class, we'll look at defeating that, and the results.

Miscellaneous Security Topics

A few short but important things to know.

Omit usernames and passwords from source code¶

Your source code will go in a public GitHub repository. Therefore, you should not put anything in there that is sensitive, personal, or has a security function. Obviously, usernames and passwords would qualify.

Similarly, using a randomly generated app.secret_key is a help,

though the fact that we are running inside the campus firewall makes

this unnecessary. However, if it weren't for the firewall, this would

be another secret to not put in the source code.

Storing Data on your Server¶

Suppose you're storing sensitive data, such as SSN or Credit Card info. You have to worry about three things:

- Is it secure on your machine? If someone hacks into your machine, can they get the data?

- Is it secure in transit? HTTPS solves this.

- Is it secure on the user's machine? For example, if it's in a cookie or a hidden form input, it may not be secure. It should not be in the URL of a GET method. Always use the POST method if anything sensitive is involved, because browsers cache URLs, servers keep logs of URLs, and people look over other people's shoulders.

A few things to consider to reduce the dangers:

-

Do you really need the data? If you use and then discard the sensitive data (for example, don't keep their credit card number on file), then the data simply isn't there to steal.

-

First line of defense is preventing them from hacking in: that is, employ good system security. Take the security course.

-

Try to make the data unusable: store credit card numbers or SSNs in encrypted form. For example, use a public key system like GPG and use the public key to encrypt the data, and only the person holding the private key can decrypt it.

-

But: Old style

/etc/passwordfiles left the encrypted (via one-way hash) password in plain sight, assuming no one could reverse the one-way password. This isn't done anymore. why?

Hidden Fields¶

Don't put information in hidden fields that you need to trust when it comes to your server. Anyone can do "view source" and see the hidden fields. They can then do a "save as" and modify the form (those hidden inputs) and submit it to your server.

General Suspicion¶

Never trust the user