The internet is not secure. Sending an email is like sending a postcard: anyone can read it along the way. The same is true of web traffic: when your browser sends a URL, it's readable by anyone along the path, and when a server sends the page back, it's readable also.

So what? What do we care if someone can read a web page? We don't. But what about sending your credit card to a server, like Amazon.com? For that, you can use https.

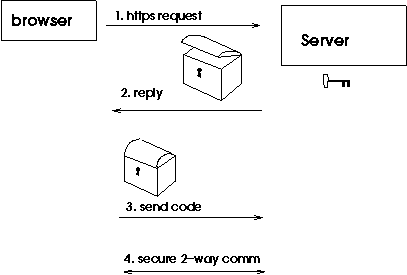

The way this works is by cryptography, which we learned about last time. Here is an outline of the mechanism:

Thanks to the secret code, any information that you send to the web site, such as your credit card number, can't be gotten by anyone along the path.

Very secure. Serious thought by lots of smart people has gone into these secret codes. It would take tremendous resources to crack the codes, and almost no one short of government agencies has those resources.

On the other hand, the web server could be hacked into. None of the things we are talking about make the web server machine any more secure. For that matter, nothing here makes your machine any more secure. In fact, a famous security guy once joked:

[It's] like using an armored truck to deliver cash from someone who lives on a park bench to someone who lives in a cardboard box.

To our knowledge, the only thefts of credit card numbers on the web have been from people hacking into web sites. No one has yet cracked the secure communications.

Moral: If you're worried, read the security information on the web site. Ideally, the personal info (credit card numbers, social security numbers, whatever), shouldn't be stored at all. Failing that, it should be stored on a separate computer.

Here's something that does work, though. It's called "spoofing," and it basically means to impersonate a web site. Spoofing takes some hacking ability, but that's common enough.

Let's make some (illegal) money:

What can be done about it? How do we deal with possible impersonation in real life? We have id cards.

A certificate is like an ID card for the web. As we saw, when your browser wants to make a secure connection to a server (such as Amazon.com), it requests a "trunk" from the server.

How does your browser know that the trunk isn't bogus? (If you're going to impersonate Amazon.com's server, you might as well supply a bogus trunk).

The answer is that the trunk is labeled with the owner's name and signed by some authority, just as a driver's license might have the state governor's signature on it. Of course, the signature is computerized (digital).

The signed, identified trunk is called a certificate.

How does your browser know that the signature on the certificate is valid? Can't the spoofer just put a bogus signature on the certificate? No: a signature can only come from a valid signing authority.

A signing authority is a company that makes money signing trunks. One is called "Verisign." The IT people at Amazon.com go to them, prove that they are valid representatives of Amazon.com, and present their trunk for signature. Verisign signs the trunk, and Amazon.com is now ready to set up a secure server.

We now have:

When viewing a secure site, you can double-click on the padlock icon to view the certificate of that site.

Do this:

Firefox>Preferences..., then click on

Advanced, select the Encryption tab,

and click on View Certificates. This displays

the certificates we've accepted, like this:

The signing authority doesn't guarantee that the company is a fine, upstanding pillar of the community, any more than a driver's license does. It just guarantees that the owner is who it claims to be.

What if the certificate is signed by an unknown authority? Then you get to engage in the following interesting dialog. To see this dialog, visit

Click here for some screen shots of what happens with unknown signers.

Certificates expire every so often, just like driver's licenses and for the same reasons.

Here's an example of a site with an expired certificate:

From the W3C Security FAQ, some more information about security certificates and even more information about security certificates [an error occurred while processing this directive]