When HTML was first introduced, there were a number of tags whose purpose was just for formatting: for example, tags that center or switch to an italic font. With HTML version 4.0, such tags were made obsolete (though most browsers still support them), in favor of a formatting technique called Cascading Style Sheets.

Customizing Your Tags

When a browser is displaying a page, there is a step of reading a

tag, such as <em> or <h1> and

then determining what the results are to look like. (This is

sometimes called rendering a page.) Each browser has a default

way of rendering a tag. For example, most browsers will render the

<em> tag by switching to an italic version of the current

font. Most browsers will render an <h1> tag by switching

to a very large version of the current font. There are several important points

to make about this:

- Different browsers don't necessarily render a tag the same way.

For example, you might find that

<blockquote>in Safari indents by a different amount than Internet Explorer does. - Some control is transferred to the user. A user can decide, via their browser preferences, what font families and font sizes they want to use, or what colors their links should be. This is a good thing.

- As the author of a web page, you can customize the rendering or

style of tags in your pages. For example, if you want the

<em>tag to look red, you can do that. The style of tags is determined by something called CSS, for Cascading Style Sheets.

CSS Style Sheets

You can specify the style of a tag using a style sheet. These style sheets can be put in (at least) three different places:

- Inline Styles. These are specified in the tag itself.

- Document-Level (Internal) Style Sheets. These are

specified in the

<head>of a document, using the special tag<style>. - External Style Sheets. These are specified in a

separate CSS file that is connected to the HTML file by the

<link>tag. We discussed this link in the HTML lecture.

Suppose that we always want <em> to be red.

(Be aware of accessibility.)

- Inline Style. You use the

styleattribute of the tag to set thecolorproperty to have the value red and thebackground-colorproperty to have the value white. (You should be reminded of the attribute/value idea in tags, but the syntax is different. With CSS, property/value pairs are separated by semi-colons, and the property ends with a colon.) Note that you should always pick both colors, in case the user's browser has specified a background color that matches your foreground color. Here's the example:this is an

which results in:<em style="color: red; background-color: white">important</em>word

this is an important word

- Document-Level (Internal) Style Sheets. You use the

<style>tag in the<head>of your document to specify the style for the<em>tag once and for all:<style> em { color: red; background-color: white; } </style>In your document (that is, in the tags enclosed by <

body>), you just use the<em>tag normally, and it will be rendered as red. - External Style Sheets. These look just like

document-level style sheets, except that you don't put the

definition(s) inside a

<style>tag. Instead, you reference the file using the<link>tag in the<head>, the same place you would use the<style>tag. Suppose we create a file calledmy-style.cssthat contains the following:em { color: red; background: white; }and we reference it in the

<head>like this:<link rel="stylesheet" href="my-style.css">

As with document-level style sheets, we can just use the

<em>tag normally from then on.

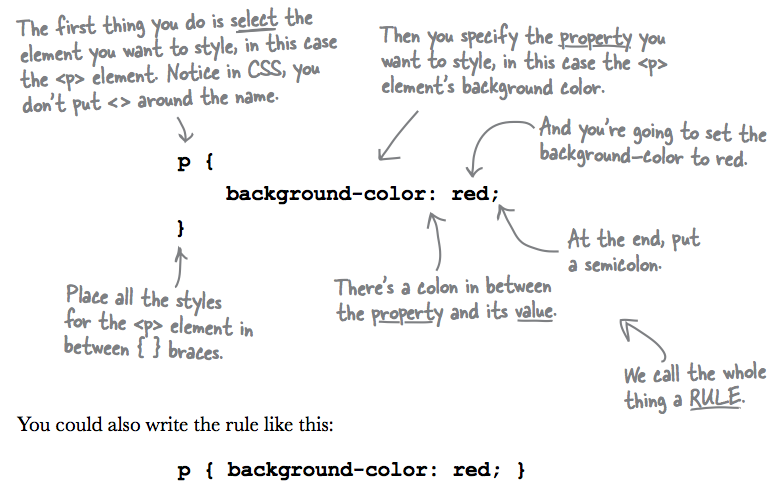

Syntax of a CSS Rule

The Head First HTML and CSS book has a good graphic for explaining the syntax of a CSS rule:

There are several facets to the syntax of a CSS rule:

- The style properties (such as

color) are followed by a colon, then at least one space, then the value of the property (such asred). If you want to specify more than one property/value pair, separate them with semi-colons. If there's only one property/value pair, the semi-colon is optional. (Many people put it in just in case they add another property/value pair later.) The order of the style properties does not matter. - For an in-line style, simply state the style properties as the

value of the

styleattribute in the HTML tag. Remember to enclose the style properties within quotation marks. - For either a document-level style sheet or an external style

sheet, the name of the element (such as

porem) that you are modifying goes first, then an opening brace, then the style properties, then a closing brace. In a CSS rule, the element to which we apply the style is known as the selector. All tags can be selectors. However, we will see more ways to define selectors in the forthcoming material. Spaces and line breaks are ignored, so feel free to format this in a visually pleasing way. As always, clear and consistent indentation is very helpful for any reader of your styles. - Document-level style sheets require the enclosing

<style>tag, while external style sheets always omit the<style>tag. - External style sheets and document-level style sheets use the

same syntax for specifying the tags, properties and values, but the

external style sheet omits the beginning and ending

<style>tags. You'll have nothing in angle brackets in an external CSS file. - CSS is a different language from HTML and therefore has a

different comment syntax in both an internal and external style

sheet. For CSS, the comment characters are

/*to begin and*/to end. Thus, for an external style sheet, you might have:/* Written by the CS110 Faculty Specifies a CSS Rule for the element

<em>*/ em { color: magenta; background-color: white; }

Some CSS Properties

Now that you know how to write style sheets, let us see some properties that you can use in these styles. One can style an element over many aspects:

- color of the text

- background of element (color, image, origin, position, etc.),

- the border that surrounds the element (its color, size, style, etc.),

- the box that surrounds the element (margin, padding, size, etc.)

- the text inside the element (alignment, spacing, direction, etc.)

- the font for the text of the element (font family, style, weight, etc.)

Examples

In the following, we give several examples of properties that are very useful for styling elements. For pedagogical purposes, we're not providing the code as text that can be easily copied and pasted somewhere else. We believe that by typing the instructions on your own, you will learn the names and values of properties, as well as potential errors that occur when one types. We strongly suggest that you use jsfiddle to try out all these examples. Before entering the code, read our questions and try to predict the answer without running the code. Then check if you were right. To use jsfiddle, enter the HTML code in the HTML box, the CSS code in the CSS box, and then click the button Run. There is no need to write a whole HTML file, only the snippets shown in the examples. Also, to see the effect of styling, the text in HTML elements doesn't have to be meaningful as in our examples.

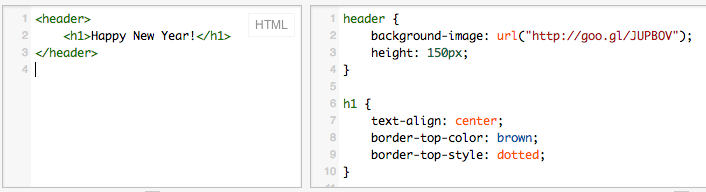

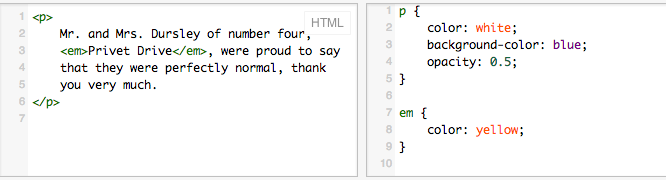

Example 1

Questions for Example 1

In the rendered result, is the background color blue? Why not? What about the color of the

text nested in <em>? Why it is not white like the rest? What does this tell

about the order in which rules are applied?

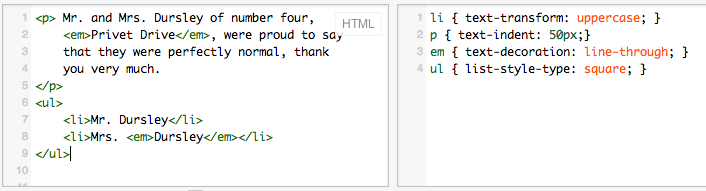

Example 2

Questions for Example 2

Try first to predict how this code will be rendered. What is the effect of each rule on every element?

How will the <em> nested in <li> look like? Then, enter this

code in jsfiddle to see whether you were right in your predictions.

Cascading

CSS has cascading

in the title because there's a

strict hierarchy that determines which specification applies

if the style of a particular tag is set in more than one

place. Suppose you specified the <em> tag

as (1) green in an external style sheet, (2) blue in a

document-level style sheet and (3) red in an inline style.

Which wins?

The simple answer is that the closest specification wins. This makes sense, because you can use the more local specifications to override the more distant, global specifications. So, inline style attributes beat document-level sheets, and document-level sheets beat external style sheets.

Furthermore, properties from enclosing elements can be inherited by the

elements inside them. Notice how, in one of the examples,

the <em> element inside

the <li> element inherits its properties.

The process of resolving all the conflicting CSS rules is called the cascade. In practice, the rules are pretty intuitive: the rule that is closer and more specific wins.

Which Style Sheet to Use?

One of the most common rules of thumb for creating clear and beautiful documents is consistency. For example, section headers should always be the same size, weight and font.

You can best achieve consistency by specifying the style far enough from the text so that the style is specified in just one place. If you have a single web page that you would like to be consistent, you should use a document-level style sheet. If you have several web pages (a web site) that you want to be consistent, you should definitely use an external style sheet. Even if your website is only a single web page but you think you might someday have a second web page using the same style, you should use an external style sheet. In short, always use an external style sheet.

Imagine that you are creating a website

for a client. For that website, you should define an external style

sheet. Then, if you or your client decides that <h1>

should be centered, <h2> should be bold and blue,

<h3> should be underlined and non-bold, and <em>

should be pink, you can do that in one place. If you later change

your mind and decide that <em> should be purple, you make

one change in one file and all of your website is consistently and

instantly changed. If you had used the local style technique, you

would have to edit every page of your site, searching for and

modifying each occurrence. This is tedious and error prone.

Caches

One of the great advantages of external style sheets is also, for a web developer, a slight bother. To understand that, you have to understand caches.

The word “cache” (pronounced “cash”) is an ordinary, but uncommon, English word (more of an SAT word for most people). However, it's used all the time by computer scientists because caches are used all the time by computers, in all kinds of ways, because caching is a general technique for speeding things up.

In particular, your web browser will cache (keep a copy of) an external style sheet in a folder on your local machine (that folder is called, of course, the cache). If the web browser needs that style file again, say on another page of your site that uses the same external style file, the browser doesn't have to re-download the file; it just grabs a copy from the cache. This makes the web browser faster.

So, why is the browser cache a problem for a web designer? Because if you make a change to the external style sheet, the web browser may continue to use the old cached copy, instead of getting the new improved copy from the server. This means that when you view your page, you won't see your changes — very frustrating.

The solution is to tell the web browser to ignore the cache when you re-load the page. In most web browsers, this is done by holding down the shift key when you click on the reload icon.

So, just remember:

When in doubt, use shift+reload

The Bigger Picture

The idea of CSS illustrates an important concept in the field of

computer science, namely abstraction. Abstraction is the

idea of saying what you want done without saying how to do it. By

leaving out the details about how to do something, you allow for some

flexibility, so that you can revise your method of doing the task

without messing up anything that depends on that task being

done. Here, we said <em> without saying what that meant,

putting elsewhere the specification of how to emphasize.

Footnote: Colors and Accessibility

Since

<em> stands for emphasis, what could be better emphasis

than putting something in red? Unfortunately, using color to convey meaning is, in fact, a

terrible idea, because some people are color-blind or even

completely blind. We'll talk more about the issue of accessibility as the need arises

throughout this course. You should always think about

accessibility when you are designing a web page, because you want your

page to be readable by anyone, not only by people with the same

physical abilities, browser software, computer display, and network

bandwidth that you have. Some websites are legally required to be

accessible. However, for the purposes of this lecture's examples,

let's suppose that using red is a sensible thing to do.