Introduction to JavaScript for Python Users¶

Python and JavaScript are actually quite similar languages, despite a lot of superficial differences. In this reading, we'll learn JavaScript in light of your knowledge of Python, pointing out similarities and differences.

One major similarity is that they are both interpreted languages, in that when the code is run, each statement is checked one at a time and executed in this fashion. This is different from a compiled language, where the code is checked all at once by the compiler before it is run. CS 230 teaches Java, which is a compiled language. Think of translation of spoken languages: There are people who translate speech on the fly while it's being spoken. There are also people who will read an entire script beforehand, translate it in one sitting, then give the entire translated speech at once. Computer science-wise, the person who translates on the fly is like an interpreted language, while the person who translates in one sitting is like a compiled language.

On another note, you may think that JavaScript is similar to Java due to their names, but make no mistake, they are quite different. Historically, JavaScript was first named LiveScript, but it was re-named JavaScript in an attempt to boost its popularity (Java was new and exciting at the time). The official name of JavaScript is actually ECMAscript, but we will continue to refer to it as JavaScript.

In this reading, we'll be highlighting some important differences between JavaScript and Python.

- Syntactic Differences

- Naming Conventions

- The JavaScript Console

- Comments

- Semi-colons

- Variable Declarations

- JavaScript Datatypes

- Null

- Undefined

- Number

- String

- Boolean

- Object/Dictionary

- Function

- Array

- Date

- Conditionals

- Functions

- Built-in Functions

- String Concatenation

- Gotchas!

- Arrays

- Loops

- Syntax Remarks

- Summary

Syntactic Differences¶

There are many syntactic differences between Python and JavaScript, and we'll review them in detail. But for now, let's just compare two functions that mean and do similar things, but look very different syntactically:

Python:

# this function is just an example; not particularly useful

def hello_world():

print("Hello world!")

print("I like CS 307")

JavaScript:

// this function is just an example; not particularly useful

function helloWorld() {

// Similar to Python's print, but console.log is most often

// used in the browser rather than an environment like Canopy

console.log("Hello world!");

console.log("I like CS 307");

}

JavaScript uses curly braces to indicate code blocks, while Python uses indentation. Also, JavaScript uses semicolons to terminate statements, while python uses newlines.

Technically speaking, the following JS code works and does the same thing:

function helloWorld(){console.log("Hello world!");console.log("I like CS 307");}

But don't do that! Humans need to be able to read your code.

(In fact, sometimes JavaScript is minified before sending it to the browser, where all unnecessary characters are removed to speed up network transmission.)

Naming Conventions¶

Another difference you may have noticed is the style of naming the

functions: hello_world versus helloWorld. The former is called

snake case and the latter

is called CamelCase. The

style is partly a matter of personal preference (I like snake case)

and are also cultural, meaning the community you are in.

It turns out that the Python community prefers snake case, while the Java and JavaScript communities prefer camel case. Note that these are just community conventions, not laws. Still, when you join a community, it's usually good to adopt its conventions. Or at least be aware.

So, how do I know these community conventions? Here are two important style guides:

Because I code a lot in both Python and JavaScript, I often make mistakes, using the "wrong" convention. The JavaScript community prefers CamelCase, so I try to code my JS in that style. I suggest you do the same, but I won't insist.

The JavaScript Console¶

Here's a short aside about some practical stuff. Our JavaScript runs in the browser, and the developer tools includes a "console", which is similar to the Python interpreter (also called the Python shell or the Python Read-Eval-Print-Loop — the REPL).

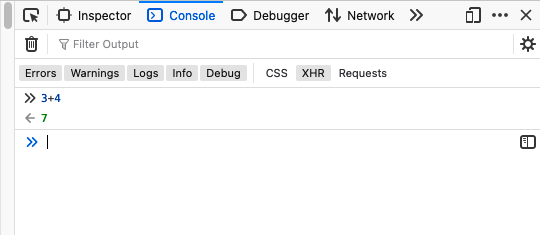

It might look like this. Notice we typed "3+4" into the console and it responded with the result of evaluating that expression.

You can get to the console using Firefox on a Mac:

- At the top bar, go to

tools > web developer > Web Console, or - Command-Option-K

If you use a different browser, just do a web search for the instructions. If you use Safari on a Mac, you may need to enable the developer tools.

To print a value from JavaScript, we use console.log(val1, val2, ...);

which prints to the browser console.

I strongly encourage you to open your JS console and try some of these snippets just by copy/pasting into the console. Here's a snippet to try:

let x = 3;

let y = 4;

let z = x + y;

console.log(x,y,z);

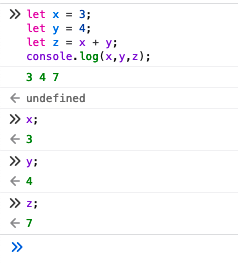

Here's what it looked like when I copy/pasted the snippet above into my JS console:

The >> is the prompt from the JS console, indicating that it's

ready for you to type something.

After copy/pasting the four lines above, I also typed in the names of each variable, and the JS console printed their values. The console colorized the code, with keywords in pink, variables in blue or purple, numbers in green and so forth. That can be helpful sometimes.

This is very like the Python REPL!

Suggestion: Students use console.log in debugging to print

relevant values, but I often see them get confused about what is being

printed or what line is doing the printing. I suggest labeling the

values, like this:

let x = 3;

console.log('x', x); // prints: x 3

instead of

let x = 3;

console.log(x); // prints: 3

The latter would be confusing if you have several console.log

statements. Another cool trick is to wrap the values with braces; this

creates a dictionary (JS object) and the printing is then very

clear:

let x=3;

console.log({x}); // prints {x: 3}

Comments¶

You probably noticed that Python uses one or more # characters to

start an end-of-line comment (a comment that goes to the end of the

line). JavaScript uses double slashes: //

JavaScript also has a syntax for multi-line comments; it's the same as Java's syntax:

/* this is a

very long comment

with multiple lines

*/

Semi-colons¶

In JavaScript, statements end in a semi-colon, unlike Python. Python would declare and assign a variable like this:

x = 3

while JavaScript does it this way:

let x = 3;

However, unfortunately, the semi-colon is optional, and the browser is allowed to guess where to put them. It almost always guesses correctly, but not 100%. Because the bugs you get when it guesses incorrectly can be difficult to debug, best practice is to include the semi-colons (though there are some who argue otherwise). But sometimes they can be safely left off.

In my examples, I try always to use the best practice and include the semi-colons, but I occasionally miss one. There are also occasions where I think the semi-colon is needless syntactic clutter and I omit it on purpose.

Variable Declarations¶

Python, we can create a variable just by assigning to a new variable name:

animal = "cat"

JavaScript requires a keyword when creating (declaring) an new

variable. Historically, that keyword was var:

var animal = "cat";

JavaScript also has two new keywords let for local variables and

const for values that will not change. In fact, it's quite common to

use const unless you are definitely going to change the value

later. So in the code below, many professional coders would use

const instead of let, since all of the variables are assigned once

and not modified. This is a useful signal to the reader. I'm trying to

get in the habit of using const when I can, but I have lots of old

code that uses let or even var.

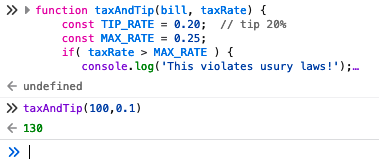

function taxAndTip(bill, taxRate) {

const TIP_RATE = 0.20; // tip 20%

const MAX_RATE = 0.25;

if( taxRate > MAX_RATE ) {

console.log('This violates usury laws!');

} else {

let tip = bill * TIP_RATE;

let tax = bill * taxRate;

let total = bill + tax + tip;

return total;

}

}

You're encouraged to copy/paste that function into the JS console and

try it out with a few arguments. If the bill is 100 and the taxRate

is 10 percent (0.10), the total payment should be 100 + 10 + 20 or

130; right? Try it and see.

The new keywords, let and const are preferred, except for global

variables, which we'll talk about later.

When you use any of these keywords, you are declaring a new

variable. Without the keyword, you are updating an existing

variable. Be clear and explicit about that: you should know when you

are creating (declaring) a new variable, so signal that to the reader

by using let or const.

Note that declaring a name to be const doesn't mean that the data

structure is read-only. The following works fine, even though we are

modifying an array that is the value of favs.

const favs = [];

favs[0] = "Raindrops on roses";

favs.push("whiskers on kittens");

console.log({favs});

The const only means we won't change the value of that name. The

following demonstrates:

const fav = 17;

fav = 42; // ERROR

JavaScript Datatypes¶

Values in JavaScript can be one of the following datatypes. You can click through to find out more technical details. (There are other types as well; this list is not exhaustive.) But we will see all of these this semester. This section introduces these types, but we'll learn more later.

Null¶

The null object is similar to Python's None object. We won't

worry about it a lot, but it will come up sometimes.

Undefined¶

A variable that is not assigned a value has the value undefined,

which is different from null. You should almost always give a

variable a value, but it's not required. Mostly, you can ignore

undefined, but you may see it sometimes.

let question = "What is the meaning of life?";

let answer; // value is undefined

console.log(question,answer);

Number¶

Numbers are straightforward. Examples like 7 or 3.14 are simple numeric literals. Python distinguishes integers from floating point values, but JavaScript doesn't typically distinguish them.

let radius = 10; // an integer

let area = 3.14 * radius * radius; // floating point values

let area_better = Math.pi * radius * radius; // use a pre-defined constant

String¶

A string is a sequence of characters enclosed by quotation marks, either single quotes or double quotes (but they must match). You may not break a string literal across a line boundary. The typical work-around is to use string concatenation like this:

let quote = 'Now is the winter of our discontent' +

"Made glorious summer by this sun of York";

JS also has template strings which are delimited by backquotes (on the same key with the tilde on most US keyboards). They are a little like Python's f-strings and triple-quoted strings, because template strings can be multi-line and can have embedded expressions that are evaluated:

const x = 3;

const y = 4;

console.log(`the sum of ${x} and ${y} is, wait for it, ...

here it is: ${x+y}`);

Boolean¶

There are two literal values for true and false: trueand false. Unlike Python, these are not capitalized.

Object/Dictionary¶

In JavaScript, objects play two roles. First, they are simple data structures of key/value pairs, virtually identical with Python's dictionaries. Here are some example usage:

const taylor = {name: "taylor swift", followers: 280_702_993};

taylor.followers++; // one more

taylor.born = 'Dec 13, 1989';

console.log(taylor);

You'll note that the syntax is a little different: you can say

taylor.born rather than Python-style taylor['born']. Actually,

JavaScript supports Python's square-bracket syntax as well, but coders

almost always use the simpler, more succinct dot notation.

Dictionaries are commonly used to pass a set of values into a function, keyword-style. Here's an example of a function that takes one argument, which is a dictionary object containing two keys:

function divide(values) {

const n = values.numerator;

const d = values.denominator;

const ratio = n / d;

const quo = Math.floor(ratio);

const rem = n % d;

console.log(`${n} divided by ${d} gives a ratio of ${ratio}

the quotient is ${quo} with remainder ${rem}`);

}

Here's an example of it in use:

divide({numerator: 7, denominator: 3});

7 divided by 3 gives a ratio of 2.3333333333333335

the quotient is 2 with remainder 1

The example above is simple, but doesn't show the technique at its best. The technique is best when there are a lot of parameters, but most of them have good defaults, so the caller only needs to specify a few, and can do them by name in the dictionary. Here's the idea:

function foo(params) {

let a = params.a || 1; // 'a' defaults to 1

let b = params.b || 2; // 'b' defaults to 2

...

return a+3*b+...z;

}

foo({a: 3, n: 5}); // other parameters use their default value

Second, JavaScript's objects can also contain methods and become the essential building blocks of object-oriented programming.

In CS 307, we will not be defining classes and methods, though you

may if you want to. We will be using lots of built-in Three.js classes

and methods, so you should be familiar with how to create instances of

classes and invoke methods on them. You learned how to do this in CS

230, so it will be straightforward. Here is some example code using

Three.js. Note the use of a parameter object for MeshPhongMaterial;

that constructor function takes a lot of parameters, but most of the

defaults are just fine.

const geometry = new THREE.BoxGeometry( 1, 1, 1 );

const material = new THREE.MeshPhongMaterial({color: 'blue',

shininess: 10,

specular: 'white'});

const mesh = new THREE.Mesh( geometry, material );

mesh.setX(4);

mesh.rotateY(Math.PI/3);

scene.add( mesh );

The above creates 3 objects using the new operator on a class

constructor function. It then invokes methods like setX and

rotateY.

Function¶

Functions are standard in any programming language. In JavaScript, as in Python, functions are first class objects, which means that they are a kind of data, meaning that they can be stored in variables, returned from functions, passed into functions as arguments, and stored in data structures. Front-end web development, including Computer Graphics, makes extensive use of that feature, so we'll see it this semester.

We've already seen lots of examples of named functions. JavaScript also has anonymous functions and arrow functions, both of which are useful at times, but we will defer looking at them.

Array¶

Like Python, JavaScript has arrays. They are created with square

brackets and commas, just as in Python. JavaScript doesn't have some

of the same notations such as negative arguments to count from the end

or getting slices by using colon notation. However, you can do that

with the new .at() method.

let primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11];

primes.push(13);

console.log('first prime', primes[0]);

console.log('last prime', primes.at(-1));

Date¶

Date:

A date object represents a moment in time (to the nearest millisecond). JavaScript has a built-in way to create date objects and to operate upon them. We will rarely need them in CS 307.

let moment = new Date('29 Jan 2017 7:14 am'); // EST

console.log('roger wins the Australian Open', moment);

Internally, times are represented in Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) which is essentially Greenwich Mean Time, though you can typically work in local time. We won't be discussing timezones and such in this course; time is a complicated thing.

Conditionals¶

In Python, indentation is crucial to conditionals. In JavaScript, we use braces to demark the beginning and end of blocks of code, and indentation just as helpful information to the reader.

Python:

# Python conditionals

if age >= 18:

print "You can vote"

if age >= 21 or (age >=18 and !currentlyInUS):

print "You can get a drink"

elif age >= 16:

print "You can get your license"

elif age == 15:

print "You can get your permit"

else:

print "No special privileges yet"

JavaScript:

// JS conditionals. Notice the logical expressions in

// parentheses, such as (age >= 18)

if (age >= 18) {

console.log("You can vote");

if (age >= 21 || (age >= 18 && !currentlyInUS)) {

console.log("You can get a drink");

}

} else if (age >= 16) {

console.log("You can get your license");

} else if (age == 15) {

console.log("You can get your permit");

} else {

console.log("No special privileges yet");

}

Here's a quick summary of the differences for conditionals and booleans:

| Python: | and | or | elif | True | False | if True: |

| JavaScript: | && | || | else if | true | false | if (true) { |

Note that there's no elif in JavaScript. You chain another if

statement on, using else if. It's only three extra characters to

type.

Functions¶

As you've seen earlier, JavaScript functions are defined using the key

word function instead of def.

function name(parameter1, parameter2, parameter3) {

return value

}

Unlike Python, JavaScript is very flexible about the arguments. Any extra arguments are ignored, and there is no error for missing arguments (though your code might not work properly).

function sub(a,b) {

return a-b;

}

sub(5,4,3); // returns 1, the 3 is ignored

sub(5,4); // returns 1

sub(5); // the subtraction will yield NaN, for Not a Number

Built-in Functions¶

Here are some useful built-in functions and their Python equivalent. Don't worry about memorizing these. We'll learn them with practice.

| Python | JavaScript | Description |

| print('x', x) | console.log('x', x) | prints a value to the console |

| no equivalent | alert(x) | pops up a window displaying the value |

| input(str) | prompt(str) | Not an exact comparison, but the Python version gives a text prompt, while the JavaScript version gives a pop-up prompt in the browser. | len(a) | a.length | Returns length of a string or array |

| str(a) | String(a) or a.toString() | Converts type to string |

| max(a, b) | Math.max(a, b) | Returns maximum of two numbers |

| min(a, b) | Math.min(a, b) | Returns minimum of two numbers |

| random.randint(a,b) | Math.random() | Returns a random number. Python returns a random number from a to b inclusive, while JavaScript returns a random number from 0 to 1. You can write a function to specify what you need, as detailed in this documentation. You need to import the random library for Python, while JavaScript's Math object is already built-in. |

String Concatenation¶

As with Python, you can concatenate two strings with the +

operator. However, in JavaScript, the values don't have to be strings. If

they aren't, they are converted to strings. So the following is quite

common:

let ans = 3+4;

alert('the answer is '+ans);

The first + is actual addition; the second concatenates the

string 'the answer is' with the value in ans (presumably 7),

converting the 7 to a string, and pops up a window with the result.

Gotchas!¶

An important fact is that you can add numbers and strings together in JavaScript, which is unlike Python. JavaScript turns the number into a string, concatenates the two together, and returns the resulting string.

let notFour = 2 + "2"; // Gets "22"

let ourClass = "CS" + 307; // Gets "CS307"

let piString = 3.14 + "1519"; // Gets "3.141519"

But the pitfall is that if you're not careful, you can get results you

didn't expect. The following code seems to add the numbers x and

y, but it doesn't:

let x = prompt('first value to add');

let y = prompt('second value to add');

let z = x + y;

alert('result is '+z);

Because prompt always returns a string, both x and y are

strings, and so z is the concatenation of the two

strings. Probably not what you intended at all!

If you want to change your string into a number, there are the

functions parseInt() and parseFloat(). The first tries to extract

an integer from a string and the latter tries to extract a floating

point number.

let three = parseInt("3.14"); // Gets 3

let pi = parseFloat("3.14"); // Gets 3.14

let x = parseInt("five"); // Gets NaN (the Not A Number value)

Thus, the earlier example can be corrected to:

let x = parseFloat(prompt('first value to add'));

let y = parseFloat(prompt('second value to add'));

let z = x + y;

alert('result is '+z);

Arrays¶

As we saw above, JavaScript arrays are very similar to Python arrays. They

have a .length property that gives the length, similar to Python's

len() function.

let primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11];

let pl = primes.length; // 5

alert(pl+' primes'); // 5 primes

What we often want to do with arrays is get and set values at different places. That's done exactly the same way as in Python. Remember, arrays start the indexing at zero:

let myClasses = ["CS 307", "ENG 103", "CAMS 240", "ECON 101"];

alert("my last class is "+myClasses[3]);

// replace ENG 103 with AFR 105

myClasses[1] = "AFT 105";

As always, you're encouraged to try these code snippets out by copy/pasting into the JS Console.

Loops¶

Usually, once you know about arrays/lists in a language, you next learn loops, so that you can do some code for every element of the array or list. JavaScript does have loops that look a lot like Java's:

// print the first 5 squares, starting at zero

for(let i=0; i < 5; i++) {

console.log(i, i**2);

}

As usual, loops combine well with arrays:

const primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11];

// print the first few primes

for( let i=0; i<primes.length; i++ ) {

console.log(i, primes[i]);

}

JavaScript also has a nice for variant, similar to Python's for in syntax:

const primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11];

// print the first few primes

for( p in primes ) {

console.log(p);

}

Syntax Remarks¶

So far, JavaScript is just like Python: the concepts are the same (variables, datatypes, functions, conditionals, etc.). The syntax is different, very different, but actually it's Python that's the odd one. JavaScript has a syntax that is derived from an ancient computer language called C, and C is also an ancestor of C++, Java, C#, Go, Swift, R, Rust, and many others, all of which are used today (as well as C itself). So, when you feel frustrated with the JavaScript syntax, remember that it's the "normal" language; Python is the oddity.

(Which is not to say that I don't like Python's syntax; I do. JavaScript's syntax is okay, too. And, yes, I get confused between the two languages from time to time.)

Summary¶

We've covered a lot of topics. Here's a brief reminder of our whirlwind tour:

- Indentation is not significant (but do it anyhow)

- braces and semi-colons are the important syntactic sugar

- The JS community prefers

camelCaseoversnake_case. - comments are

//or/* and */ - datatypes

null(likeNone)undefined- Number (integers and floating point)

- String

- Boolean (

trueandfalse, uncapitalized) - Object: both dictionaries and objects with methods

- Function: first-class. Can be named or anonymous

- Array:

let primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11 ]; - Date: a particular date and time. More later

- variable declarations. Always declare a variable when you create it.

letfor variables that will or might changeconstfor variables that won't or shouldn't change

- conditionals:

if( boolean_expr ) { then_block } else { else_block } - boolean operators:

&&for and: both expressions are true||for or: either expression is true (or both)

- functions:

function name(arg1, arg2) { function_body } - built-in functions:

console.log(arg1,arg2)prints the arguments to the consolealert(arg)pops up a window that shows the argumentprompt(str)pops up a window that requests a string from the user. Shows thestrexplaining what is wantedarray.lengthreturns the length of the given arrayx.toString()converts the value ofxto a string and returns itMath.max(a,b)returns the larger of two numbersMath.min(a,b)returns the smaller of two numbersMath.random()returns a random number between 0 and 1

- string concatenation is done with the

+operator. Works on non-strings, which can be a trap:x+yis not necessarily add. - Arrays. indexed from zero, just like in Python and Java. Uses square bracket notation.

favs[0] = primes[3]; - Loops: Just like Java's, pretty much

- Functions are first class values. That means

- you can pass them as arguments to functions (callback functions)

- you can store them in variables and other data structures

- you can return them as values from functions

Whew! That's a lot. But remember, much of this is based on ideas you know (variables, conditionals, functions, arrays) just in a different form.