Vallor defines honesty as a respect for truth in a complex, interconnected world. In the technosocial context, Vallor emphasizes that practicing honesty extends beyond simply telling the truth—it requires moral expertise in communicating the truth well. A strong embodiment of the technomoral virtue of honesty involves the communication of information ethically, reliably, and appropriately, especially in an age dominated by digital media and surveillance technologies (Vallor, 2016, pp. 121–122).

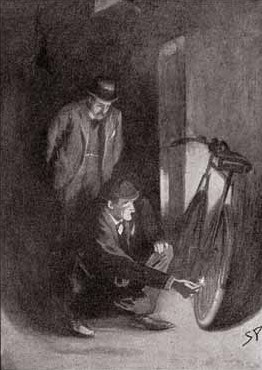

Sherlock Holmes, iconic detective created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, is known for his ability to solve cases through logic and observation. Holmes is clear-minded, relying only on reasoning separate of emotional influence and a relentless pursuit of the facts.

Holmes exemplifies Vallor’s conception of honesty as more than truth telling. It involves a moral responsibility in how the truth is discovered and communicated. Holmes himself proclaims he is guided by the importance of “not allow[ing] your judgment to be biased by personal qualities” (Taliaferro & Le Gall, 2012, p. 134). His refusal to let bias or emotion cloud his judgment demonstrates the “virtue of honesty” through the “primacy assigned by Sherlock to objectivity and truth” (Taliaferro & Le Gall, 2012, p. 137). Holmes’ meticulous examination of what is the truth is a form of honesty that mirrors how the ethical communicator must handle information in today’s technosocial context.